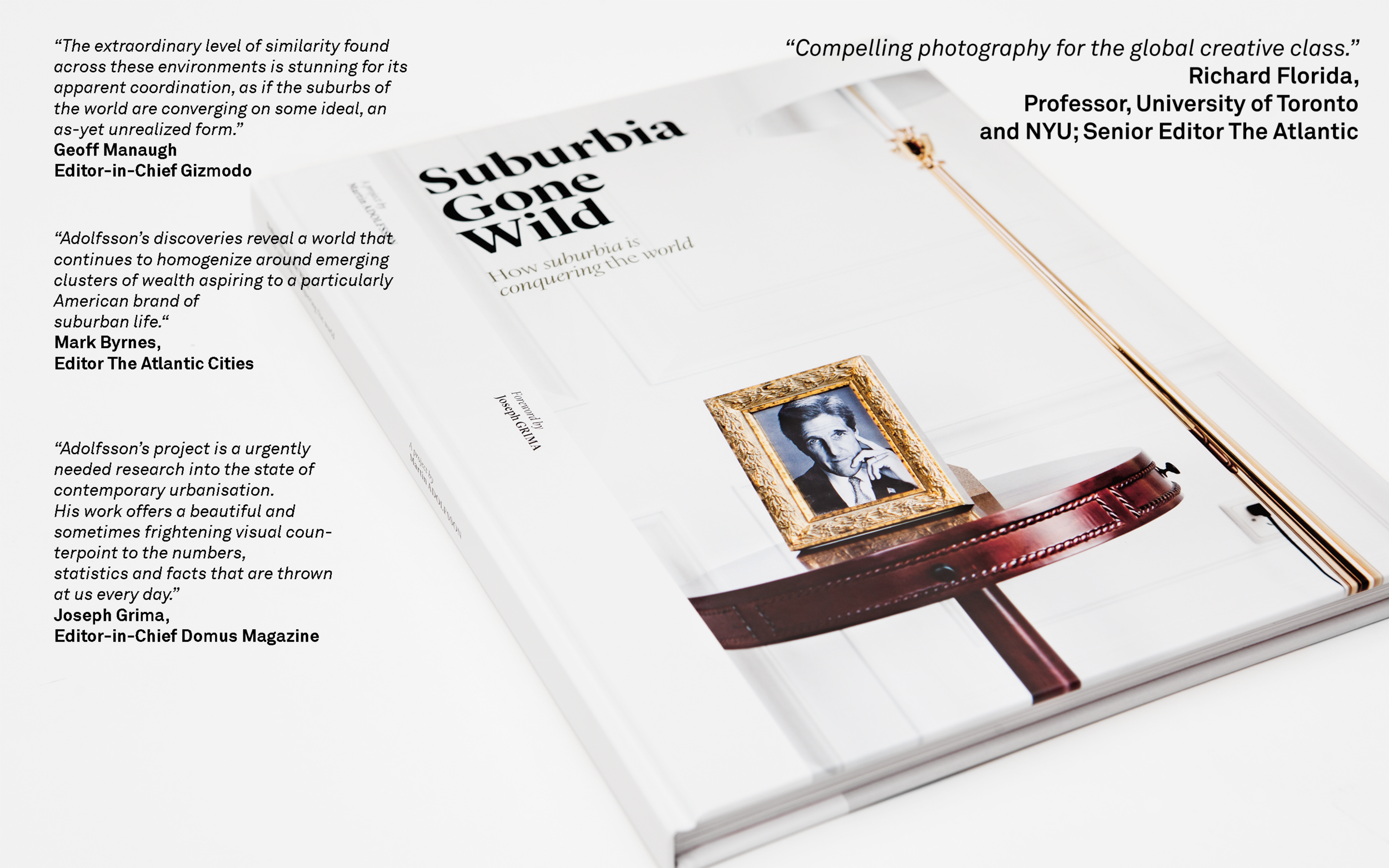

Suburbia Gone Wild

Suburbia Gone Wild

Disguised as a home buyer, I photographed model homes built for the new upper middle class in emerging economies --including the suburbs of Bangkok, Shanghai, Bangalore, Cairo, Moscow, Johannesburg, São Paulo, and Mexico City.

̌

Text by Tina Essmaker

Suburbia Gone Wild is the culmination of a six-year photographic study of model homes in emerging economies, undertaken by photographer, Martin Adolfsson. His collection of images have an uncanny resemblance to the American experience of suburbia, however, none of these photos were taken on American soil.

Instead, these images document a strange phenomenon that is cropping up around the globe: urban sprawl is becoming a trend in developing cities as suburbs are being constructed to house a new upper-middle class.

In 2006, Martin experienced this phenomenon firsthand. He was traveling to Thailand for a photography workshop and as the plane descended into Bangkok's airport, he was struck by an unexpected sight: a large development of cookie-cutter houses that resembled structures in his home country of Sweden.

The grouping of homes piqued his curiosity. Determined to learn more, Martin hired an assistant and, together, they ventured to the outskirts of Bangkok to locate the development.

After a day of trial and error, navigating through the congested, chaotic streets of Bangkok, they discovered Parkway Chalet, a newly constructed suburb named after cottages typically found in the Swiss Alps.

For the next three days, Martin went back to Parkway Chalet with his tripod and camera to photograph the landscape, the homes, and their inhabitants. On the final day, he noticed an empty house on the outskirts of the development.

He approached the terrace, where a sign in Thai was positioned next to French doors that were wide open to reveal the immaculately decorated interior. Not able to read Thai, Martin was unsure of the sign's message; he didn't know if it was welcoming him, telling him to stay out, or something altogether different.

With no one around to offer assistance, Martin stood outside and began to photograph. Then, in a moment of boldness, he stepped over the threshold and into the living room. From there, he took as many photos as possible, not knowing if his activities were illegal or if someone would be arriving shortly to escort him out.

However, nothing happened; no alarms sounded and no one came. Martin was completely alone, captivated, and intrigued by his very first encounter with a model home.

Martin speculated about whether or not similar homes existed in other emerging economies. After doing some research, he learned that these homes did exist elsewhere; American sprawl had reached other continents

Not knowing what to do with his newfound interest in this subject matter, Martin put his ideas aside and moved forward with life. In 2007, he left Sweden to move to New York for a photography residency at the School of Visual Arts.

He continued to think about photographing model homes from time to time and although he first considered it a crazy idea, he soon began to think it was actually possible.

In 2008, he applied for grant money to help fund this project, and between 2008-2009, he was awarded grants from three entities: The Swedish Arts Grants Committee, The Association of Swedish Professional Photographers, and Längmanska Kulturfonden.

With the financial backing to execute his idea, Martin started planning trips to several cities. However, he ran into a crucial challenge early on. Getting access to the homes was going to be more difficult than initially thought because most developers would not allow cameras or photography on site.

Thus, Martin decided to take an unconventional approach to access the homes. No permission or permits to shoot would be obtained. Instead, Martin hired either a male or female assistant in each city to pose as his partner and act as a translator. Together, they played the charade of a well-to-do couple in the market to buy a home.

Martin concealed a handheld DSLR camera in a leather holdall and while his assistants distracted the realtors, he was free to photograph the homes' interiors. Because of the covert nature of the shoots, none of the shots have been lit and none of the interiors were altered in any way.

Over the course of six years, beginning with Bangkok in 2006, Martin traveled to eight cities: Shanghai, Bangalore, Cairo, Moscow, Johannesburg, Mexico City, and São Paulo. He began the journey with a hunch that what he would find in each city would be similar to what he saw in Bangkok.

Thus, he decided to take an objective approach to photograph the subject matter to present it as a study. It was a deliberate move not to include any people, signs, or objects that would indicate the location of the photographs. Instead, Martin wanted to give the viewer a sense that each image could have been taken anywhere, even in his or her own backyard.

Thousands of images later, Martin had a realization. He wasn't just studying the commonalities among model homes in emerging economies; he was studying the shift in the identity of this new upper middle class around the globe.

For them, the migration to the suburbs represents more than a changing economy. It signifies the search for a new identity and, perhaps, even an identity crisis.

The constructed suburban enclaves are devoid of cultural influences, traditions, and customs associated with the larger national identity and the homogeneity of the photos suggests that those living in these newly fabricated suburbs around the world may have more in common with each other than with their fellow countrymen.

Every architect, Rem Koolhaas once said, carries the utopian gene. In many ways, the history of architecture is the reassembly of the fragments of this naive and irrepressible desire to make the world a better place through countless infinitesimal material gestures, within each of which an entire architectural cosmology is embedded.

As with any form of ideologically-driven activity, the practice involves conflict, and the interfamilial feuds of the history of Architecture are as epic and acrimonious as any crusade. Yet what architects themselves so frequently forget is that the battlefield of Architecture upon which these doctrinal struggles generally unfold is what software developers call a "sandbox"—a controlled environment far removed from the chaotic, uncontrollable, and largely untheorised landscape of everyday life that is the realm of architecture with a lower case A.

This book is a chronicle of Martin Adolfson's explorations in this "other" landscape. The spaces it documents are populated by buildings that appear unconcerned with—or perhaps even unaware of—the murderous jihads thundering on within the walled garden of Architecture; they serenely go about the business of giving form to the Reality an ever-increasing proportion of the world's population inhabits.

More precisely, this book is the documentation of the architectural by-product of the birth of a new, expanding global demographic—the opulent upper middle class born to booming economies in every corner of the planet. Shanghai, Bangkok, Bangalore, Cairo, Moscow, Johannesburg, Sao Paolo, and Mexico City: cities rocked by the shockwave of new and highly concentrated wealth, struggling to compensate for the disbalance between widespread poverty and pockets of vast opulence.

Just as NASA documents with its telescopes the fiery explosions that accompany the birth of supernovas in distant galaxies, Adolfson's camera captures the architectural byproduct of this new class as it explodes outwards from the booming financial centers of newly-developed economies, unfurling into the landscape an architectural fantasy-reality directly sampled from a TV soap.

The emphasis on the domestic sphere lends a particular immediacy to the photographs, which resonate with the conflicting sentiments generated by the intimacy of the domestic and the mild perversity of the value-system they represent, structured around an abstract pastiche of status-symbols torn from the pages of a lifestyle magazine.

Flipping through the pages of this book, one could imagine one is looking at images of a single city, an assemblage of landscapes, details, interiors sampled from neighborhoods mildly differentiated by a superficial veneer of regional inspiration. (An inverse of sorts of Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, in which many cities turn out to be one city).

Even the names of the neighborhoods share a magnificently generic vocabulary that noncommittally hints at the distant and exotic, folding the entire history of architecture into a mildly-flavored petri dish: Mantri Espana (in Bangalore, India); St Andrews Manor (in Shanghai, China); Parkway Chalet (in Bangkok, China).

So is this a landscape purged of ideology? Almost. The irony is that this "polyglot architecture", capable of effortlessly donning the superficial trappings of any regional vernacular, was actually made possible by one of the most ideologically-inspired technological innovations in the history of Architecture with a capital A, namely Le Corbusier's Maison Dom-ino, conceived to execute his vision for an efficient, flexible, dense urbanism—precisely the reverse of what it in fact generated.

The Maison Dom-ino was first conceived in 1914 as a versatile response to the emergent demand for housing in war-torn Europe: for the first time in the history of architecture, the plan was completely liberated from the constraints imposed by the structural system, providing endless variations in the arrangement of interiors, thereby perfectly articulating the Five Points of Architecture in an affordable precursor to the opulence of Ville Savoye.

Maison Domino was designed as a building prototype for mass production, and in the heroically exaggerated perspective of Le Corbusier's grayscale rendering of a slab-and-column structure, one can easily identify the DNA of the Purist city. It is a deeply idealistic project, combining the aesthetic principles of Purism with the structurally optimized technology of reinforced concrete, allowing total freedom in the layout of the plan.

The landscapes in Adolfson's photos are a portrait, exactly one century later, of this ideologically-driven technological innovation subsumed by reality, wrested from the prescriptive control of its author, and unleashed in full developer-driven force onto the landscape.

As if to emphasize the genealogical proximity between this new global vernacular and its Modernist ancestry, Adolfson adopts the language of architecture photography to narrate the brutal reality of the de facto state of contemporary "architecture"—however much we may struggle to recognize it as such. Welcome to the new global vernacular of the age of technological supremacy on the landscape.